Epidemic characteristics of alcohol-related liver disease in Asia from 2000 to 2020: A systematic review and meta-analysis

Funding information

This work was sponsored by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81 972 265, 82 170 602) and the National Natural Science Foundation of Jilin Province (20200201324JC, 20200201532JC)

Handling Editor: Alejandro Forner

Abstract

Background and Aims

To systematically summarize the prevalence of alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) and the alcohol-attributable proportions of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cases in Asia.

Methods

The Embase, PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane, CINAHL, WanfangMed and China National Knowledge Infrastructure databases were searched from 01 January 2000 to 01 December 2021 for reports of ALD prevalence and alcohol-attributable proportions of liver cirrhosis/HCC in Asian populations. Study characteristics were extracted, and meta-analyses were conducted.

Results

Our literature search identified 13 studies reporting the ALD prevalence, 62 studies reporting the alcohol-attributable proportion of liver cirrhosis and 34 studies reporting the alcohol-attributable proportion of HCC. The overall prevalence of ALD was 4.81% (95% confidence interval [CI] 3.67%, 6.09%). The ALD prevalence was higher in men (7.80% [95% CI 5.70%, 10.19%]) than in women (0.88% [95% CI 0.35%, 1.64%]) and increased significantly over time from 3.82% (95% CI 2.74%, 5.07%) between 2000 and 2010 to 6.62% (95% CI 4.97%, 8.50%) between 2011 and 2020. Among 469 640 cases of liver cirrhosis, the pooled alcohol-attributable proportion was 12.57% (95% CI 10.20%, 15.16%). Among 82 615 HCC cases, the pooled alcohol-attributable proportion was 8.30% (95% CI 6.10%,11.21%). Significant regional differences were observed in alcohol-attributable proportions of liver cirrhosis and HCC.

Conclusions

The prevalence of ALD and the proportions of alcohol-related liver cirrhosis and HCC in Asia are lower than those in western populations. However, a gradual increasing trend was observed over the last 21 years. ALD is likely to emerge as a leading cause of chronic liver disease in Asia.

Abbreviations

-

- ALD

-

- alcohol-related liver disease

-

- CI

-

- confidence interval

-

- HCC

-

- hepatocellular carcinoma

Key Points

- The overall prevalence of ALD was 4.81% in Asia and was higher in men than in women.

- The pooled alcohol-attributable proportions of liver cirrhosis and HCC were 12.57% and 8.30%, respectively, in Asia.

- The ALD prevalence and alcohol-attributable proportion of HCC in Asia increased over the past two decades.

- The alcohol-attributable proportions of liver cirrhosis and HCC varied among different countries and regions.

1 INTRODUCTION

Nearly half of the global burden of liver disease is associated with excessive alcohol consumption,1 and the spectrum of alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) includes steatosis, steatohepatitis, fibrosis, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). In 2010, approximately 500 000 deaths globally were attributed to alcoholic cirrhosis, which accounted for 47.9% of all cirrhosis-related deaths, and an additional 80 000 deaths were caused by alcohol-related HCC.2 Moreover, approximately one-third of all cases of primary liver cancer globally are related to alcohol consumption, with marked variations between countries and regions.3-6

The Asia-Pacific region is home to more than half of the global population and the location of a reported 62.6% of global deaths because of liver diseases.7 Prior studies analysing the liver disease burden in Asian populations have focused either on single countries or regions, individual years, or a subset of the most common aetiologies, such as hepatitis B or C virus (HBV or HCV, respectively).8-12 According to the 2018 Alcohol and Health Report by the World Health Organization, the Western Pacific Region showed the second-highest increase in alcohol consumption with a projected per capita consumption of 0.9 litres of pure alcohol by 2025. Given the observed increases in alcohol consumption, the disease burden of ALD in Asia is likely to grow accordingly. However, to date, there have been no systematic reviews of the prevalence and outcomes of ALD in a broad Asian population. The aim of this study was to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis to establish the overall ALD prevalence and alcohol-attributable proportions of liver cirrhosis and HCC in Asia. Our analysis also included stratification by sex, country/region and time period to provide further insight into the ALD burden in Asia.

2 METHODS

2.1 Literature search

Two authors (Xu HQ and Xiao P) independently searched the PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Cochrane, CINAHL, Wanfang MED and China National Knowledge Infrastructure online databases for relevant articles published between 01 January 2000 to 01 December 2021, using search terms developed in collaboration with a medical librarian without language restrictions. This systematic review conducted two sets of literature searches for the prevalence of ALD and the proportion of alcohol-attributable liver cirrhosis/HCC in Asian populations, independently. In the first set, we searched for cross-sectional studies that included patients with ALD diagnosed according to local diagnostic criteria. The detailed search strategy is shown in Table S1. In the second set, articles were included if they presented cross-sectional studies in Asian patients with liver cirrhosis, liver cancer or HCC diagnosed using established diagnostic criteria and if they provided data on the alcohol-attributable proportions of liver cirrhosis and liver cancer/HCC. The detailed search strategy is shown in Table S2. The same two authors independently screened all articles, first by title and abstract and then by review of the full-text review to identify eligible studies. Disagreements about study inclusion were discussed with a third reviewer (Zhang FY) and resolved by consensus.

2.2 Data extraction

From all relevant articles, two researchers (Xu HQ and Liu T) independently extracted the authors' names, year of publication, country, investigation period, sample source, study design, assessment of liver cirrhosis, number of observed ALDs, number of total participants, basic characteristics of patients and numbers of liver cirrhosis cases and HCC cases attributed to alcohol consumption. Where necessary, the numbers of ALD cases within studies were re-calculated if only the rates and total numbers of patients were included in the articles. When duplicate data were identified, we excluded the study with the smallest sample size. Discordant results regarding study data were resolved by discussion between the two authors or consultation with a third senior researcher (Gao YH). We assessed the quality of included studies using an assessment scale based on the Combie scale, which is specifically designed to evaluate cross-sectional studies.13 Answers to the quality appraisal items were defined as Yes (1 point), No (0 point) and Not Applicable or Unclear (0.5 point). The maximum score on the Combie scale is 7. Studies with a score of 6–7 are deemed high quality (Grade A); those with a score of 4.0–5.5 are considered fair quality (Grade B); and those with a score of 0–3.5 are ranked as low quality (Grade C). The present study included only studies with a quality assessment of grade A or B, excluding those with grade C. In addition, we also excluded studies with fewer than 200 cases of cirrhosis and fewer than 100 cases of HCC.

The overall prevalence of ALD and alcohol-attributable proportions of liver cirrhosis and primary liver cancer/HCC cases were calculated with single-proportion meta-analysis, using ‘meta’ in R. We estimated the heterogeneity among studies using Cochran's Q statistic (p < .05 indicates moderate heterogeneity) and the I2 statistic (≥50% indicates moderate heterogeneity). Heterogeneity among data also was evaluated using Cochran's Q test and the I2 statistic. If significant heterogeneity (I2 > 50%, p < .1) was found between studies, the data were evaluated with a random-effects model; otherwise, a fixed-effects model was used. When significant heterogeneity was identified, we ran a meta-regression using the random-effects model to study the impact of moderator variables. Meanwhile, subgroup analyses were carried out to investigate sources of heterogeneity. We used Egger's test to assess publication bias. Sensitivity analysis was used to assess the robustness of the pooled results.

3 RESULTS

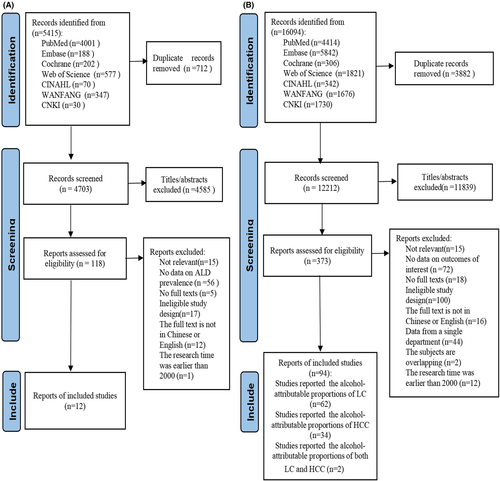

In the first set of database searches, we screened and systematically analysed articles related to the prevalence of ALD. Initially, 5415 articles were identified, and after removal of duplicates, 4703 articles were retained. Screening of the titles and abstracts led to the exclusion of 4584 ineligible studies. Finally, 12 articles describing 13 study populations fulfilled the criteria and were included in the systematic review and pooled analysis (Figure 1A; Table S3). In the second set of literature searches, we screened and systematically analysed articles related to the proportion of alcohol-attributable liver cirrhosis/HCC. A total of 16 094 articles were identified, and after removal of duplicates, 12 212 articles were retained. Screening of the titles and abstracts led to the exclusion of 11 839 ineligible studies. Finally, 62 studies related to alcohol-attributable liver cirrhosis (469 640 participants) and 34 studies related to alcohol-attributable HCC (82 615 participants) were included after full-text reading (Figure 1B). Detailed information for all included studies is provided in the supplemental files (Tables S4 and S5). All articles were published in English or Chinese; thus, no translation was necessary. The results of study quality assessment for the included studies are presented in Tables S3 to S5.

3.1 Prevalence of ALD in Asia

The data on ALD prevalence were all from China and South Korea, including 10 studies in China and 3 studies in Korea. From the 13 studies (n = 101 434; Table S3) reporting the ALD prevalence, the overall ALD prevalence was 4.81% (95% confidence interval [CI] 3.67%,6.09%; Table 1). The ALD prevalence in China was 5.15%(95% CI 3.97%, 6.48%), and that in South Korea was 4.09% (95% CI 0.92%, 7.25%). No statistically significant differences were identified in ALD prevalence between China and South Korea (p = .45). Eight studies (n = 74 039) were included in a subgroup analysis of ALD prevalence from 2000 to 2009, and the ALD prevalence during this period was found to be 3.82% (95% CI 2.74%, 5.07%); Table 1). Five studies (n = 27 395) were included in a subgroup analysis of ALD prevalence from 2010–2020, and the ALD prevalence during this period was higher (6.62% [95% CI 4.97%, 8.50%]) than that during 2000–2009 (p < .01). Comparison of the male and female populations of 11 studies revealed that the ALD prevalence was higher in men (7.80% [95% CI: 5.70%%, 10.19%]) than in women (0.88% [95% CI: 0.35%%, 1.64%], p < .01; Table 1). Considerable heterogeneity was observed among the studies reporting the overall ALD prevalence (I2 = 98.5%) and among those included in the subgroup analyses (I2 > 95.0%; Table 1). However, no significant publication bias was identified in these studies (Egger's test p = .78). Sensitivity analysis suggested that the results of this meta-analysis were stable (Figure S1).

| Studies (n) | Participants (n) | Case of ALD (n) | Prevalence (CI 95%) | I 2 | p-value of subgroup difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n = 13) | 101 434 | 4924 | 4.81% (3.67%, 6.09%) | 98.50% | |

| Sex | |||||

| Female (n = 11) | 40 088 | 349 | 0.88% (0.35%, 1.64%) | 96.00% | <.01 |

| Male (n = 11) | 56 300 | 4365 | 7.80% (5.70%, 10.19%) | 98.70% | |

| Country | |||||

| China (n = 10) | 68 024 | 3462 | 5.15% (3.97%, 6.48%) | 97.50% | .45 |

| South Korea (n = 3) | 33 410 | 1462 | 4.09% (0.92%, 7.25%) | 99.50% | |

| Study period | |||||

| 2000–2009 (n = 8) | 74 039 | 3003 | 3.82% (2.74%, 5.07%) | 98.00% | <.01 |

| 2010–2020 (n = 5) | 27 395 | 1921 | 6.62% (4.97%, 8.50%) | 96.10% |

- Abbreviations: ALD, alcohol-related liver disease; CI, confidence interval.

3.2 Proportion of alcohol-attributable liver cirrhosis in Asia

Overall, 62 studies reporting the alcohol-attributable proportion of liver cirrhosis cases were included in this study (Table S4). The pooled alcohol-attributable proportion of liver cirrhosis was 12.57% (95% CI 10.20%, 15.16%) among the 469 640 participants with liver cirrhosis (Table 2). Considerable heterogeneity was observed among all studies reporting the alcohol-attributable proportion of liver cirrhosis (I2 = 99.8%). Sample size, study period and country of the paediatric populations were selected as potential covariates for the multivariate regression models, which were available from all of the included studies. The multivariate meta-regression analysis showed that only Country/Region (p < .05) was significantly correlated with proportion of alcohol-attributable liver cirrhosis in Asia (Table S6).

| Total liver cirrhosis cases (n) | Alcoholic liver cirrhosis cases (n) | Proportion of alcohol-attributable cases (95% CI) | I 2 | p-value of subgroup difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n = 62) | 469 640 | 71 779 | 12.57% (10.20%, 15.16%) | 99.80% | |

| Study period | .901 | ||||

| 2000–2009 (n = 15) | 44 735 | 5793 | 10.35% (7.43%, 14.43%) | 98.70% | |

| Around 2010 (n = 31) | 293 366 | 41 152 | 12.78% (9.41%, 16.57%) | 99.90% | |

| 2011–2020 (n = 16) | 131 539 | 24 834 | 14.75% (9.54%, 19.96%) | 99.90% | |

| Country/Region | <.001 | ||||

| Iran, Turkey(n = 2) | 3792 | 95 | 2.48% (2.00%, 3.00%) | 0.00% | |

| China, Singapore, Malaya, Israel (n = 48) | 219 709 | 18 061 | 9.48% (7.50%, 11.92%) | 99.10% | |

| Japan (n = 5) | 165 955 | 30 106 | 19.11% (15.04%, 23.97%) | 99.60% | |

| South Korea (n = 5) | 69 663 | 19 562 | 23.15%(12.91%, 35.31%) | 99.90% | |

| India (n = 2) | 10 521 | 3955 | 37.12%(31.60%, 42.82%) | 97.50% |

- Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

We further analysed the alcohol-attributable proportion of liver cirrhosis in different countries/regions. The alcohol-attributable proportion of liver cirrhosis was highest in India (37.12% [31.60%, 42.82%]) followed by South Korea (23.15% [12.91%, 35.31%]) and Japan (19.11% [15.04%, 23.97%]). Much lower proportions were found among 48 studies among China, Singapore, Malaya and Israel(9.48% [(7.50%, 11.92%)]). The lowest proportions were found in Iran and Turkey (2.48% [2.00%, 3.00%] (Table 2). The heterogeneities were considerable in all these subgroups except in Iran and Turkey.

We also analysed the alcohol-attributable proportion of liver cirrhosis during different study periods. From 15 studies that reported the alcohol-attributable proportion of liver cirrhosis during the period from 2000 to 2009, the pooled alcohol-attributable proportion of liver cirrhosis was 10.35% (7.43%, 14.43%). From 31 studies that reported this proportion for the period around 2010, the pooled alcohol-attributable proportion of liver cirrhosis was 12.78% (9.41%, 16.57%). The pooled alcohol-attributable proportion of liver cirrhosis was 14.75% (9.54%, 19.96%) for the period from 2011 to 2020 from 16 studies (Table 2). The pooled alcohol-attributable proportion of liver cirrhosis among different study period were not significantly different(p = .90). Considerable heterogeneities were observed in all these subgroups(I2 > 98.5%). (Table 2).

No significant publication bias was identified in the overall studies (Egger's test p = .88) and subgroups (Egger's test p > .05). A sensitivity analysis synthesizing the overall proportion of alcohol-attributable liver cirrhosis from 62 studies showed that the results were stable (Figure S2).

3.3 Proportion of alcohol-attributable HCC in Asia

From 34 studies that reported the alcohol-attributable proportion of HCC (Table S5), the overall pooled alcohol-attributable proportion of HCC was 8.30% (95% CI 6.10%, 11.221%); Table 3. Considerable heterogeneity was observed among all studies reporting the alcohol-attributable proportion of liver cirrhosis (I2 = 98.8%). Sample size, study period and country of the HCC patients were selected as potential covariates for the multivariate regression models, which were available from all of the included studies. The multivariate meta-regression analysis showed that Country/Region and study period were significantly correlated with proportion of alcohol-attributable HCC in Asia (p < .05) (Table S7). The alcohol-attributable proportion of HCC was highest in India (16.79% [7.93%, 28.06%]) followed by Singapore(12.58% [11.44%, 13.81%]) and Japan (8.79% [5.66%, 13.673%]). The alcohol-attributable proportion of HCC was lowest in countries of China, Korea, Malaysia, Qatar and Turkey (5.80% [4.04%, 8.26%]). We also analysed the alcohol-attributable proportion of liver cirrhosis during different study periods in Asia. From 14 studies that reported the alcohol-attributable proportion of HCC during the period from 2000 to 2009, the pooled alcohol-attributable proportion of liver cirrhosis was 6.90% (4.84%, 9.83%) (Table.3). From five studies that reported this proportion for the period from 2011 to 2020, the pooled alcohol-attributable proportion of HCC was 16.78% (6.85%, 35.60%) which is higher than 10 years ago (Table.3; Table S7).

| Total HCC cases (n) | Alcohol-related HCC cases (n) | Alcohol-attributable proportion (95% CI) | I 2 | p-value of subgroup difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 82 615 | 6203 | 8.30% (6.10%, 11.21%) | 98.80% | - | |

| Study period | .189 | ||||

| ~2009(n = 14) | 22 493 | 1557 | 6.90% (4.84%, 9.83%) | 95.40% | |

| Around 2010(n = 15) | 44 049 | 2519 | 8.90%(5.77%, 12.72%) | 98.50% | |

| 2011–2020 (n = 5) | 16 073 | 2127 | 16.78% (6.85%, 35.60%) | 99.50% | |

| Country | <.001 | ||||

| China, Korea, Malaysia, Qatar, Turkey (n = 18) | 13 317 | 966 | 5.80% (4.04%, 8.26%) | 95.50% | |

| Japan (n = 5) | 63 049 | 4169 | 8.79% (5.66%, 13.673%) | 99.60% | |

| Singapore (n = 1) | 3013 | 379 | 12.58% (11.44%, 13.81%) | - | |

| India (n = 10) | 3236 | 689 | 16.79% (7.93%, 28.06%) | 98.70% |

- Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

Considerable heterogeneity was observed among all studies reporting the alcohol-attributable proportion of HCC (I2 = 99.7%) as well as those included in the subgroup analyses (I2 > 95.0%; Table 3). No significant publication bias was identified among these studies (Egger's test p = .37). Sensitivity analysis suggested that the results of the overall meta-analysis were stable (Figure S3).

4 DISCUSSION

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, we determined that the overall prevalence of ALD among adults in Asia was 4.81% (95% CI 3.67%, 6.09%). The ALD prevalence was much higher in men (7.80% [95% CI 5.70%, 10.19%]) than in women (0.88% [95% CI 0.35%, 1.64%]). The pooled alcohol-attributable proportion of liver cirrhosis cases was 12.57% (95% CI 10.20%, 15.16%) among 469 640 participants with liver cirrhosis across various regions in Asia, and the overall alcohol-attributable proportion of HCC cases was 8.30% (95% CI 6.10%, 11.21%).

The overall prevalence of ALD in Asia is difficult to assess accurately, because large-scale epidemiological surveys of ALD are not available for many countries or regions. Nevertheless, the present study represents an effort to estimate the prevalence of ALD in the Asian population and different subgroups based on the existing data and provides a summary report on the situation of ALD in Asia. Our finding that the prevalence of ALD in men is significantly higher than that in women is in line with the social characteristics of socioeconomic status and alcohol consumption level of men and women in Asia.31 The increase in the ALD prevalence from 2000–2009 to 2010–2020 also is consistent with previous research.17 For example, the prevalence of ALD increased in the USA from 11.78% in 1988–1994 to 15.66% in 1999–2004 and finally to 14.78% in 2005–2008.18 Moreover, the age-standardized mortality owing to ALD also increased from 7.76% in 2007 to 10.35% in 2016 according to results from the US Census and National Center for Health Statistics mortality records.19 Still, the value for the overall prevalence of ALD in China and Korea determined in this study (4.81% [95% CI 3.67%, 6.09%]) is lower than values reported for the USA (6.2%–8.8%) and European countries (6%).14-16 The main reason for this is that the total alcohol consumption per capita varies among different regions. According to World Health Organization (WHO) data, alcohol consumption in Europe has been on a downwards trend in recent years, and the current per capita average is about 9.8 L(litres of pure ethanol). Alcohol consumption in the Americas and the Mediterranean region was stable at around 8 L from 2005 to 2016. In contrast, alcohol consumption is increasing in the Western Pacific and South-East Asia regions. Taking China and India as examples, the total alcohol consumption per capita in China has increased from 4.1 L in 2005 to 7.2 L in 2016, and the total alcohol consumption per capita in India has increased from 2.4 L in 2005 to 5.7 L in 2016.21 Although the total alcohol consumption per capita in the Asia-Pacific region currently is still lower than that in Europe and the African region, the harm caused by alcohol consumption in the Asia-Pacific region may be not lower or may be even higher than that in Europe and North America. This may be caused by socioeconomic differences between the Asia-Pacific region and Europe and North America. Studies have shown that lower socioeconomic status leads to a 1.5- to 2fold higher mortality for alcohol-attributable causes compared with all causes.20 In other words, the “harm per litre” of alcohol is substantially greater for poorer drinkers than for richer ones on an individual level.21 Another potential cause for lower rates of ALD in Asia could be the increased frequency of mutation in the acetaldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2) gene, which has been detected in nearly 8% of the global population, and more frequently in East Asia.22 Mutation of the ALDH2 gene can lead to acetaldehyde accumulation in the body after alcohol consumption, which can cause symptoms of discomfort, thereby limiting excessive alcohol consumption to some degree.

Liver cirrhosis is an important stage in the development of ALD and the leading cause of liver-related death in the Asia-Pacific region, accounting for 48.2% of such deaths in 2015.23 Excessive alcohol consumption is a major risk factor for liver diseases, and particularly, liver cirrhosis.6, 24 Our results showed that among the aetiologies of liver cirrhosis in Asia, alcohol accounted for approximately 12.57% of cases. The proportion of alcohol-related cirrhosis varies greatly among different countries and regions, which is related to differences in per capita income, drinking habits, epidemic of other aetiology and the genetic background of the population in different regions.

The second most common cause of ALD-related deaths in the Asia-Pacific region is liver cancer, which accounted for 43.6% of all ALD-related deaths in the region in 2015.23 Excessive alcohol consumption is well established as an independent and strong risk factor for the development of HCC. Chronic alcohol use exceeding 80 g/d for longer than 10 years increases the risk for HCC by fivefold.27 Our results showed that 8.3%(95% CI 6.10%,11.21%) of HCC cases in Asia were attributed to excessive alcohol intake, which is much lower than the proportion reported for Western high-income areas and the global average (30%).3 In 2015, studies found that excessive alcohol consumption contributed to 10% of HCC cases in Australasia, 43%–46% in central Europe, 32% in eastern Europe, 32% in western Europe, and 37% in North America.3 A subsequent study published in 2018 identified alcohol abuse as the etiopathogenetic factor in 28% of HCC in Australasia, 35% in central Europe, 39% in eastern Europe, 30% in western Europe and 32% in North America.28 Moreover, in the past two decades, the alcohol-attributable proportion of HCC in Asia has gradually increased from 6.90% (4.84%, 9.83%) in 2000–2009 to 16.78% (6.85%, 35.60%) in 2011–2020. This may be related to the effective prevention and treatment of chronic viral hepatitis in recent years. Multiple studies have shown that HBV/HCV infection accounts for the largest proportions of cirrhosis and liver cancer cases in many Asian countries, which directly leads to a large proportion of HCC caused by viral hepatitis.16, 24 As the preventive effect of HBV vaccination and the therapeutic effect of direct-acting antiviral drugs for HCV infection continue to have a larger impact on these conditions, the proportions of alcohol-attributable liver cancer are expected to increase in the future.25, 26

In recent years, the prevalence of metabolic diseases such as obesity and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease has increased rapidly in the Asian population, and the interaction between alcohol consumption and metabolic diseases such as obesity, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and diabetes remains unclear. Studies have shown that light-to-moderate alcohol consumption increases the risk of adverse outcomes in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) patients.29, 30 The alcohol-related Global Burden of Disease study supported that the safest level of alcohol drinking is none for patients with NAFLD and other metabolic diseases.31 Therefore, the increasing prevalence of ALD in Asia and the current proportions of alcohol-attributable LC/HCC are immediate concerns that should be widely recognized, and related research is urgently needed.

The present study has both strengths and limitations. Our meta-analysis provides the most comprehensive assessment to date of the prevalence of ALD and the proportion of alcohol-attributable liver cirrhosis/HCC in Asia. However, the present study is limited by the paucity of data from some relatively large Asian countries. Because we also included the Chinese literature in our screening, the results from studies in China accounted for a relatively large proportion of cases included in our analyses, which may have created a bias in the weight of the situation in China. Additionally, the minimum ages of study participants were not completely consistent across all of the included studies. In two studies, the minimum ages of the surveyed populations were 0 and 7 years. However, because the percentages of individuals in the lower age group were very small (<200 of 18 837 participants were younger than 18 years), we can likely ignore the influence of these cases and consider the sample representative of Asian adults. Furthermore, this meta-analysis was limited by the fact that all the included studies were cross-sectional in design and did not collect detailed demographic characteristics, total alcohol per capita consumption, the genetic background of the study participants, per capita income, etc. The above variables all contribute to the heterogeneity of ALD prevalence and the proportions of alcohol-attributable LC/HCC. Therefore, high heterogeneity was observed among the included studies, even among our subgroup analyses.

In summary, the present study provides the first meta-analysis of the overall prevalence of ALD and the alcohol-attributable proportions of liver cirrhosis and HCC in Asia. The results showed that the ALD prevalence and the proportions of ALD-related liver cirrhosis and HCC are significantly lower in Asia than in Western countries but have followed overall increasing trends in recent years. Effective health interventions to reduce the risk of alcohol abuse should be implemented in Asia as soon as possible to reverse these trends and prevent ALD. In addition, early ALD screening in heavy drinkers is important to prevent the development of adverse outcomes, including end-stage liver disease.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.